EGYPTIAN MUSEUM

Egyptian museum with several rooms displaying works of art, ancient Egyptian gods, sarcophagi...

Like the rest of the country, the Egyptian Museum is cramped for space. It won't be for much longer, as some of its works are due to be moved to the Grand Egyptian Museum, which is due to open in part in 2024. The works presented below will undoubtedly be organized differently once the famous Grand Museum has fully opened its doors. In particular, the entire Treasury of Tutankhamun will be relocated, impacting a large part of the Egyptian Museum's museography.

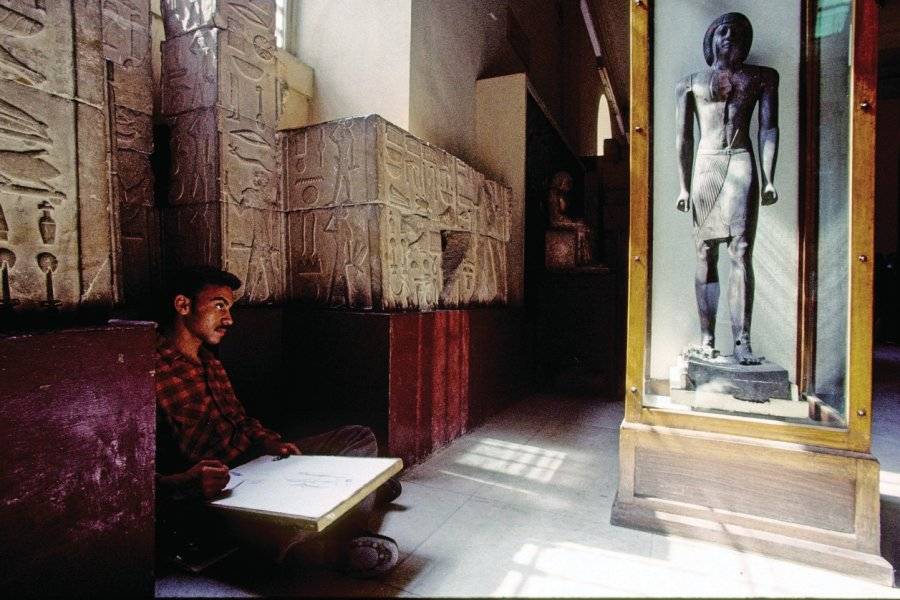

If you're an enthusiast, a single visit won't be enough to tour the hundred thousand or so antiquities on display. Especially as the lack of space and the dizzying profusion of pieces will put your nerves to the test, and after two hours, nothing will hold your attention any longer: you'll wander wearily over marvels that deserve more sustained attention. After this visit, the temples and tombs of Upper Egypt will seem quite empty!

The façade and gardens. Built in 1896 by Marcel Dourgnon, this is arguably Cairo's first true Egyptian museum. Auguste Mariette, to whom Mohammed Ali had entrusted the direction of the first antiquities department, had the ambition of building this museum and devoted part of his life to the project. He died in 1881, and his successor commissioned Dourgnon to construct the building we know today, to which Gaston Maspero transferred the collections in 1902, the year the museum was inaugurated.

Now surrounded by buildings whose height exceeds its elegant dome, the museum was built in the new district of Boulaq, once marshy and flooded by the river, which Khedive Ismaïl transformed into a chic, Western-inspired district at the end of the 19th century. The building's neoclassical facade reflected the Khedive's taste for France and Italy. In the gardens to the west, a bronze man wearing a tarbouche keeps watch over his mausoleum: he is Auguste Mariette, to whom the protection of Egyptian antiquities owes a great deal. Visitors stroll through the garden littered with monumental statues and embellished by a papyrus-planted pond.

Directions for the visit. The rooms on display contain the museum's most remarkable exhibits, which a well-informed visitor must have admired if he or she has only two hours to spare. The other rooms on the first floor, which are not listed, contain Hellenistic statuary, while the rooms on the second floor, which are not mentioned, contain sarcophagi and ritual or everyday objects. The art objects on the second floor, less impressive if we consider only the magnificence of the royal goldsmiths, will appeal to lovers of ceramics and woodwork, and to the sensibilities of everyone who will recognize in them the expression of human creative genius, fashioned some millennia ago. A visit to the rooms is punctuated by the rhythm of the heartbeat. Here, you're not visiting a succession of shaped and heaped stones, you're meeting quasi-gods in the form of almost living statues.

First floor: Predynastic period (4000 - 3000) and Protodynastic period (2920 - 2770). Room 43. Few Predynastic objects are known from Nagada I and Nagada II and III, apart from a few stelae engraved on ivory and terracotta bowls, including a remarkable example decorated with crocodiles in relief. The great exception is the Narmer palette, which is placed at the hinge of the two periods and attributed to dynasty "0", a quirk of Egyptology. This double-sided schist plaque is engraved with an elaborate representation of Pharaoh, with well-thought-out symbols of power and authority. It is not, however, the first image of Pharaoh that we have - contrary to what the guides will declaim in front of Narmer's palette - and we can refer to the 2003 "Pharaoh" exhibition at the Institut du Monde Arabe, which presented a shale statuette from Nagada I of a bearded man wearing the crown of Upper Egypt (Musée de Lyon).

The Narmer palette, which celebrates the reunification of the two kingdoms, displays the symbols of Pharaoh as they would be reused by all subsequent dynasties. On one side, bearded Pharaoh, wearing the crown of Upper Egypt (the bonnet), holds in his right hand a mace that he is about to smash on the head of an enemy kneeling before him. A much smaller dignitary stands behind him, wearing his sandals. On the other side, Pharaoh is wearing the attributes of Lower Egypt, towering over decapitated enemies. On both sides, the bull's heads represent the goddess Athor and surround Pharaoh's name.

The protodynastic period, with its first two dynasties, is richer in these objects, which are presented in this first room of the museum.

It is interesting for art lovers and visitors alike to note that the materials used were the same as those employed by the successors of these first pharaohs: gold, raw or glazed earthenware, carnelian and amethyst for jewelry; ivory, wood and clay for everyday objects; schist, steatite, alabaster, limestone and pink granite for statues.

Old Kingdom (2649 - 2065). Rooms 31, 32, 36, 37, 41, 42, 46, 47, 48. The works exhibited in these rooms transcend the political events of the Old Kingdom, a period divided into eight powerful dynasties that gave Egypt a dominant regional position. The Pharaohs most remembered are Djoser, Khéops, Unas, Téti and Pépi1er.

47. Djoser, builder of the Saqqarah funerary complex with the help of the brilliant architect Imhotep, is depicted seated in a painted limestone statue, wearing a wig and a false beard. Pharaoh is then shown in the midst of three triads in Menkaura greenschist. Pharaoh, his torso inflated, holds in his right hand that of the goddess Athor, and in his left hand that of a local nome, i.e. a jurisdiction.

The mastabas at Saqqarah contained painted limestone statuettes of Pharaoh and his family, whose colors have been extraordinarily spared the wear and tear of time.

46. In Old Kingdom Egyptian statuary, there is a desire to show the humanity of the people represented, whether they be Pharaoh and his family, or simple workers who are sculpted, like this young bearer of colorful basketwork. The funerary sculptures touch us with their closeness: Ak, seated on a black-painted limestone seat, is surrounded by his wife's right arm, and eternity retains only this tender, intimate love between them, which was never meant to end. The seated scribe unashamedly shows off a full belly and the chest of a man who eats well; there's no artificial quest to camouflage the human being.

41. Amidst painted limestone bas-reliefs taken from the Meïdoum mastabas, near the pyramid of the same name, is an alabaster statue of the same Menkaura seated on his throne, showing the veining peculiar to this stone, which is very sensitive to heat and can blacken easily on exposure. The Meïdoum geese were removed from the mastaba of the pyramid of the same name, a hundred kilometers from Guiza. This painted plaster is exceptionally colorful.

42. Kephren's face, made of diorite, the second hardest stone after diamond, is one of the best-known of Egypt's kings, since it is his face that adorns the red 10 LE banknotes found in every pocket. But the encounter with the original is overwhelming. The museum leaves a seated statue of the king to be contemplated. The sculptor's mastery of his art borders on perfection. In this way, we admire both the work and the model. All that's missing is Képhren's breath to stand up, alive. Clad in a simple linen loincloth and covered with his headdress, he is almost naked. And yet, his majesty naturally imposes itself. The stone, worked in this way, expresses the king's humanity to perfection. Horus, the falcon god, is sculpted as an extension of the head; he can only be seen in profile. He protects Pharaoh. Equally touching is the wooden statue of Ka-Aper, who was given the nickname "village mayor" or "oumda" in Egyptian, because the statue resembled the Saqqarah notable where it was found. It was made over 4,500 years ago..

32. The variety of works on display does not detract from their diverse quality. The seated statues of Rahotep and his wife Nofret, in painted limestone, look as if they were made the day before, so fresh are the colors. We admire the composite necklace Nofret wears, and her husband's moustache reminds us of the faces of young Egyptians in the Nile Delta. What can we say about the humor of the sculptor and his models when the dwarf Seneb, his wife and children are depicted? It's a family photograph: Seneb is seated as a scribe on a bench, while his wife embraces him; too small to have his legs dangling, it's his daughter and son who are sculpted in their place!

37. This room is particularly devoted to the reign of Khufu. An ivory statuette of the king, builder of the Great Pyramid on the Giza Plateau, found in Abydos, stands alone in a display case. The room's funerary furnishings do not belong to Pharaoh, whose chamber is still being sought, but to his mother, buried in a nearby small pyramid.

Middle Kingdom (2040 - 1550). Rooms 26, 21, 22, 16, 11. Works of art from the Middle Kingdom were inspired by and refined the features of the preceding period. Thebes became the empire's political and religious capital, and artists had new palaces, temples and tombs to adorn with statues and objects. The politico-religious turmoil had repercussions on art, which became even more of a means of asserting Pharaoh's authority. The tombs of the Valley of the Kings were dug deeper, welcoming powerful monarchs who were buried with increasingly sumptuous treasures. A monumental pink granite statue of Sesostris III can also be admired in the museum's main hall.

26. The monumental statue of Mentuhotep II, in painted sandstone, comes from the funerary temple of Dar al-Bahari, on the west bank of Thebes. His typical seated position is also that of Osiris, arms folded. He wears the imposing double crown, and appears to have been unfinished. The black color of Pharaoh's skin may also be a reference to Osiris' death.

21. This room contains a number of bas-relief treasures. The pillar of SesostrisI, made of fine limestone with painted parts still visible, comes from the Temple of Amun at Karnak. On each side of the pillar, Pharaoh is embraced by a different god: Horus, Amon, Aton, Ptah. This pillar was discovered in the courtyard of the hiding place. The Dedusobek funerary stele, also in painted limestone, shows a common family scene in which the pharaoh, carrying his heir on his knees, offers libations to the deceased. The limestone statue of Sesostris I, in addition to Pharaoh's perfect plasticity, is interesting for the two sides of the throne where Lower and Upper Egypt are figuratively represented.

22. The same king is represented, this time in painted Lebanese cedar wood covered in gold. The craftsman has combined the cedar's gilded wood with the golden-white paint of the sovereign's loincloth and bonnet, creating a harmonious whole.

We also admire the small naos of Nakht, which contained a statue of this dignitary; this object became particularly fashionable during the 12th Dynasty.

16. Imposing black granite statues are the jewels of this hall, notably the sphinx of Amenemhat III. This sphinx belongs to a group of seven pieces found in Tanis, the ancient capital of Lower Egypt. Pharaoh's unusual headdress, false beard and round, closed face give him a strong immanent power. A group depicting the same Pharaoh with the personification of the god Nile, seated next to each other, is surprising in its mastery of symmetry.

11. There is only one work of art worthy of note in this room, the wooden statue of the ka. This extraordinary wooden statue, covered in gold leaf and semi-precious stones, still has its funerary chapel in the same blond wood.

It was found at Dachour, in the funerary complex of Amenemhat III. The faith of the time considered each person to be made up of five elements: the shadow, the spiritual form or akh, the power or ba, the name and the vital force or ka. It was to this last element that offerings were made to the deceased pharaoh, in the form of food. This statue of Amenemhat III thus served to ensure that Pharaoh's life force would endure in death.

New Kingdom (1550 - 664). Rooms 12, 11, 7, 8, 3, 13, 9, 10, (14, 15, 20, 25). If the New Kingdom was rich in artistic diversity, it's undoubtedly because the monarchs of the 18th and 19th dynasties were often people of strong character: Hatshepsut, Amenophis IV, Seti I, Ramses II. The Tutankhamen treasure, though exceptional, is another story. The dynasties that followed, from the Third Intermediate Period (1075 - 664), were no longer of major artistic interest for Egyptian antiquities, and even less so the so-called Late Period, which preceded the Hellenistic period.

12. The style of the New Kingdom does not forget the tenderness of statuary from earlier times, as witnessed by the seated group of Tutmosis IV with his mother, in black granite rock, where the arms are crossed between the king and his mother. This statue is posthumous as far as the mother is concerned, having died at the time the work was made, as the hieroglyphs describe. The diorite statue of Tuthmosis III, also found in the courtyard of the hiding place by French Egyptologist Legrain, presents the features of a young king with an open, smiling face. This room contains the chapel and the votive statue of Hathor, in painted sandstone. Among many other masterpieces, the monumental statue of Tutankhamun, in black granite rock, stands out. He was young at the time, and had not yet ascended the throne, as shown by the braid of his hair.

11. Queen Hatshepsut's majestic head, in painted limestone, comes from the temple she built at Dar al-Bahari and completes the series of Osirid pillars that adorn the now-restored third façade. It's a fine example of the use of art for political and religious ends; the sovereign was widely contested, even though she was only to be regent of the kingdom until Tuthmosis III came of age.

3. This room is a fine tribute to Amarna art as it was developed during the reign of Amenophis IV, whose second reign name was Akhenaten. The faces of Nefertiti in bas-relief on limestone, or of Amenophis IV with his colossal sandstone pillars, respond to the new canons of statuary of this monotheistic parenthesis in the history of Egyptian antiquity. Fool or genius, surrounded by parents and advisors who encouraged him in his choice to break with the faith of his fathers, it is extraordinary to note that a new artistic style immediately imposed itself and stuck to the new religious order. It is said that Amenhotep IV's bloating and elongated, gaunt facial features were the mark of an illness from which the monarch was suffering. The stele showing Pharaoh, Nefertiti and their daughters worshipping Aten is complete: the stripes of the unique solar god have not been broken, whereas many similar representations have been cursed in this way.

9 and 10. These two rooms contain various statues of Ramses II and his father Seti I. The latter gave Egypt its name. The latter gave ancient Egypt some of its most elegant bas-reliefs, both in his temple on the west bank of Thebes, and in certain rooms of Abydos. His son continued this work, giving it a more martial style, but retaining a purity of form. We can admire a black granite rock bust of Ramses II, when he was still young; his linen robe is of rare delicacy. Somewhat in the manner of Narmer, who is said to have created the artistic symbols of Pharaoh's power, a fragment of painted limestone bas-relief shows Ramses II, twice as tall as his enemies, holding them by the hair, while he holds a flail in the other hand. In the same room, Ramses II is depicted as a child, crouching before the god Horus, who seems to wrap him in his protective wings.

The hall. The pieces on display here correspond to all eras, but have in common the fact that they are monumental, and have therefore been placed in this gigantic central space in the manner of the stone statues and sarcophagi on show.

A colossal group of Amenhotep III and his wife, seven meters high, dominates the room. The blond limestone again shows Pharaoh embraced by his wife's right arm. Their daughters stand at their feet.

Two sandstone sarcophagi of Queen Hatshepsut are on display. Why two vaults for one and the same person? The first was built when she was royal consort, the second when she became queen. A third had also been carved and was to contain the regent.

The magnificent pink granite tomb of Merenptah, which was rejected by Psusennes I , is also on display. It was in this tomb, brought back from Tanis, that the silver and gold sarcophagus on display on the museum's second floor, in the Tanis treasury, was found.

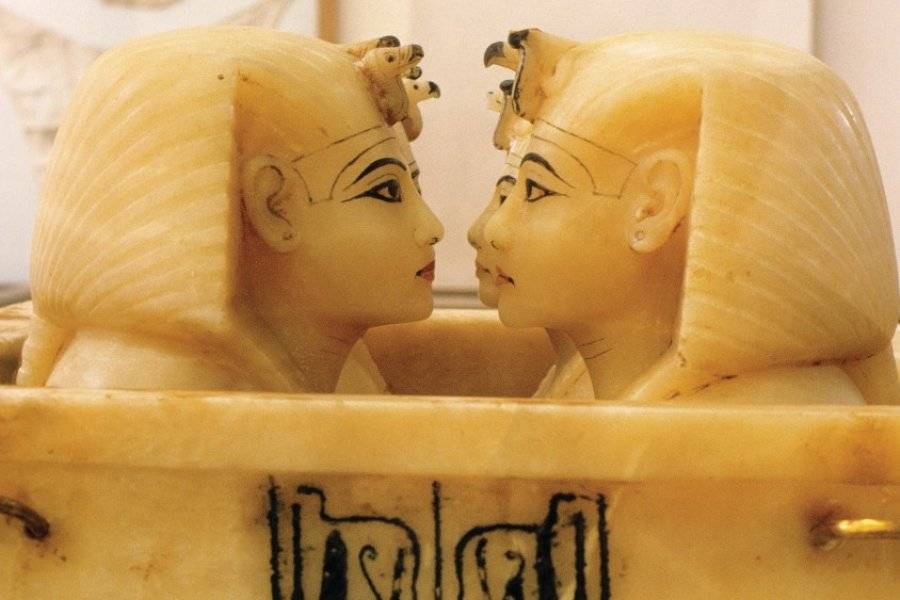

The second floor: the funerary treasure from the tomb of Tutankhamun (18th dynasty, 1333 - 1323). Rooms 45, 40, 35, 30, 25, 20, 15, 10, 9, 8, 7, 13, 3. Although all Egyptian rulers were buried with a number of ritual objects intended for their eternal life, no New Kingdom tomb has ever been found with all its contents, as was Tutankhamun's tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1922. The two galleries devoted to this young monarch's tomb are fascinating for the magnificence of their contents and for the insights they provide into the furnishings of a royal tomb.

45. Two gilded wooden statues, representing the ka (life force) of the deceased, were placed in the first mortuary chamber. They guarded the entrance and were destined to receive ritual offerings. Discovered today, they were surrounded by a linen cloth that has decomposed. Two other gilded wooden statues are on display in this room. One depicts Pharaoh wearing the crown of Lower Egypt, the bonnet, the other the crown of Upper Egypt. In both cases, Pharaoh holds in his hands the insignia of his dignity, including the flail. The tomb also contained a gilded wooden votive shield depicting Pharaoh holding a lion by its tail - the enemies - as he prepares to strike it with a sword.

40. Tutankhamun is depicted either on a leopard, representing the Milky Way or the underworld dominated by Pharaoh, likened to the sun; or on a papyrus boat, in hunting stance, ready to strike a hippopotamus with his javelin: the animal we can guess symbolizes evil. Among other treasures, this room contains a beautiful painted wooden chest depicting Pharaoh on his chariot, fighting enemies. The ouchebtis, small statues bearing the effigy of Pharaoh, which were placed in the tomb, were intended to assist the king in his daily tasks throughout eternity.

35. Several dozen blue earthenware ouchebtis are on display in this room, which also houses the king's throne. This splendid wooden structure, covered with thick gold leaf, silver, glass paste and semi-precious stones, is accompanied by a similarly crafted footrest. The back of the throne depicts the king seated, while his wife, standing, tenderly touches his arm. The attributes of the Pharaoh are all represented: vulture, snake, lion. The footrest is decorated with the bodies of enemies whom Pharaoh symbolically dominates. You can also stop in front of a wooden naos plated with gold and silver, the sumptuousness of which leaves you speechless.

20. Rarer objects are displayed in this room. These include a set of alabasters, including a bowl-shaped lamp with an engraved and colored interior depicting Pharaoh and his wife, a perfume container, a small basin and its boat, bowls and vases. Some of the finest objects in the treasure trove were made from the purest, non-veined alabaster.

In the same room, you can also admire elements of the miniature gilded wooden fleet of 18 vessels that Pharaoh was to take with him on his journey to eternity, and which were to carry all the treasure contained in the royal tomb.

10 and 9. A collection of three gilded wooden funerary beds is on display here. Their zoomorphic shapes differ from one another. The lion-shaped bed features only the elements of this feline, as does the cow-shaped bed, which represents the original Earth of life on earth. The third bed is a hybrid made up of hippopotamus heads, a leopard's body and crocodile tails; it symbolizes the devourer of corpses who appears at the weighing of souls. In the same room are displayed an armless mannequin of Tutankhamun, as well as a superb dog resembling Anubis, god of the dead, whose black and gilded wooden statue was found at the entrance to the tomb. Last but not least, we can admire the casket and its four alabaster canopic vases which preserved the king's viscera, and which were stored in the gilded wooden box displayed beside it, surrounded by four goddesses whose open arms form a prayer link for Pharaoh.

8. Four gilded wooden caskets, which covered the sarcophagus like Russian dolls, were found in Pharaoh's burial chamber. They are displayed one after the other. It took archaeologists eighty-four days in 1922 to dismantle them. The first shrine had already been opened by looters who didn't have time to continue their theft; the seals remained on the other three. It is thought that these caskets have symbolic forms: the first is the tent where the king recovers his powers in the afterlife, the second and third are in the image of predynastic temples in the South, the fourth in the image of predynastic temples in the North. The walls are covered with magical inscriptions from the Book of the Dead.

13. Among Pharaoh's objects in the tomb's antechamber was a ceremonial wooden chariot, covered in gold, semi-precious stones and glass paste. The shaft of the chariot is decorated with two heads of enemies to magnify Pharaoh's power.

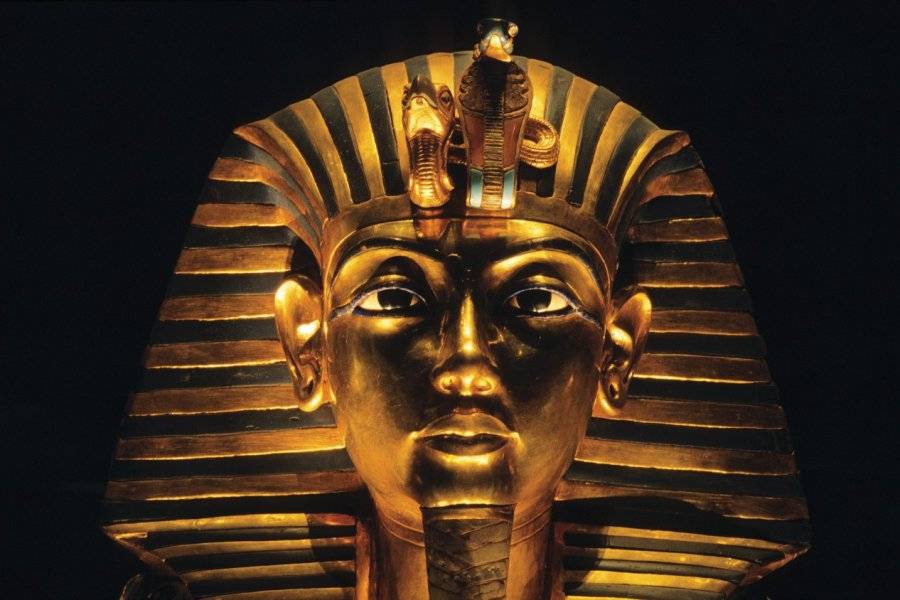

3. The goldsmith's pieces contained in the sarcophagus and the gold treasure. In this room, illuminated only by artificial light, Tutankhamun's funerary mask, made of gold, lapis lazuli, carnelian, quartz, obsidian, turquoise and pâte de verre, is on display. Pharaoh wears the nemes, the white and blue linen wig cover, encircled by an orle bearing the images of the serpent and the vulture; they are the guardians of the two Egyptians. The king's ears are pierced, a remnant of the Amarna period and its aesthetic canons.

There are several pendants. The first, in the form of two gold cartouches, was designed to hold ointments. Young Pharaoh is also depicted in a similar manner, twice, in gold and blue pâte de verre, seated on the ground, eating. A gold necklace supports a gold and stone falcon. This necklace was glued to the mummy's bandages, along with a necklace depicting three lapis lazuli scarabs on one side and Pharaoh chosen by Amun-Ra.

Pharaoh also wore a large saltire representing the god Horus and was surrounded by a gold and stone mesh corset. On one side, a scene depicts him facing Amun, on the other a curious representation of a scarab with the body of a falcon and carrying a carnelian sun. He is surrounded by the crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt. Pharaoh's flail and scepter are made of bronze, gold, glass paste and wood.

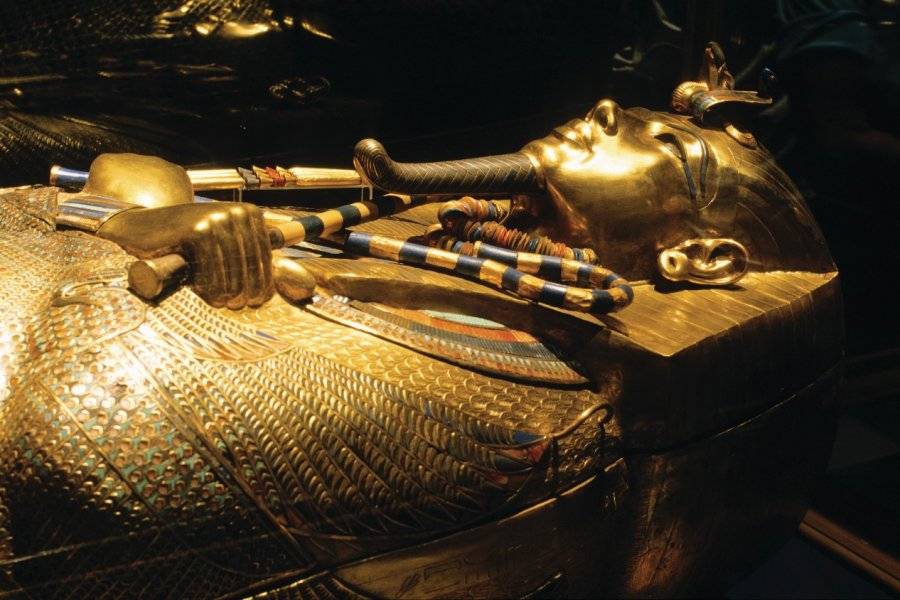

Two of Pharaoh's three gilded wooden sarcophagi are on display in the museum, the third being in Pharaoh's tomb in the Valley of the Kings. Here we admire the inner sarcophagus, entirely in gold, as well as the second sarcophagus in gilded wood, entirely covered with a mosaic of turquoise, carnelian and lapis lazuli.

Gold and silverware. Room 4. This small room, next to the Tutankhamun mask room, contains a collection of goldsmith's and silversmith's pieces from two princesses, Sarthathor and Mereret, found at Dashur.

The majority of the pieces on display were not worn by the princesses during their lives; they were made for their tomb and draped in the bandages of the mummy that was then sealed in the sarcophagus.

Highlights include a Horus head in gold and obsidian, and a sumptuous silver mirror with a handle in gold, obsidian and semi-precious stones.

The collection of necklaces, bracelets, long necklaces and pendants provides an invaluable insight into the art of royal jewelry-making at the time. Gold and silver tableware can also be admired.

The treasure of Tanis. Room 2. The city of Tanis, now located in the Nile Delta, was home to a number of temples and tombs, where numerous objects were found in 1929. Ramses II was responsible for most of the main temple.

Well-known is the mask of Psusennes I, made of gold, lapis lazuli and pâte de verre, which graced the cover and poster of the 2003 "Pharaoh" exhibition at the Institut du Monde Arabe. He wears white and blue linen nemes and the protectiveuraeus of Lower Egypt. Another major piece is the silver sarcophagus of the same king, a remarkable piece of goldsmithery.

Woodwork: rooms 12, 17, 22, 27, 32, 37.

Sarcophagi: rooms 21, 31, 36, 37, 48.

Yuya and Tuya: room 43. The treasure trove of this minister and his wife buried in the Valley of the Kings is almost complete. These are the only two mummies left in the museum.

Daily life: room 34.

Ostraka and papyrus: room 24.

Ancient Egyptian gods: room 19.

Fayum portraits. Room 14. The Cairo Museum contains a number of portraits from Fayoum, the oasis to the south-east of the Egyptian capital, rich in monuments of Egyptian antiquity and a Roman past, as evidenced by the funerary portraits, painted on wood and placed on the head of the deceased swaddled in diamond-shaped braided bandages.

Did you know? This review was written by our professional authors.

Members' reviews on EGYPTIAN MUSEUM

The ratings and reviews below reflect the subjective opinions of members and not the opinion of The Little Witty.

Oui, le nouveau sera plus grand, plus lumineux, plus aéré, plus près des pyramides, mais cela ne sera jamais pareil que cet endroit rempli d'objets fabuleux qui nous replongent dans nos rêves d'enfants archéologues.

Mais aussi les sarcophages, les bijoux, les outils...c'est un musée inégalable.